Replace Working/Non-Working Ratios with Deploy & Develop Allocations

Is the working to non-working balancing act obsolete and flawed? Without a doubt, this ratio — and its impact on effective spend management — is a controversial topic among C-suite executives and agency leaders. The ratio often makes headlines in investor calls when major cuts in non-working spend are announced, leading to budget reductions or reinvestment in media budgets. At its core, this discussion is central to leaders trying to demonstrate their responsible use of marketing budgets in an increasingly competitive and cost-cutting environment. This ratio has been increasingly scrutinized by experts and industry organizations, such as the Association of National Advertisers (ANA) and the World Federation of Advertisers (WFA), in recent years. The evolving advertising and media landscape has profoundly changed the dynamics of brand investments, and best practices for advertisers are emerging. A new advertising world requires adjusting the specifics of this formula to make better budget decisions.

Working and non-working for Dummies

Let’s start with a non-intimidating description of this budgeting approach:

• Working spend represents the amount of marketing budget allocated to the actual distribution and optimization of marketing content across different channels of communication, such as TV, print, outdoor, and digital. It is what the consumer ultimately sees or experiences. Content might include social, ad technology, data, insight, production costs, trafficking, distribution, talent payroll, assets storage and management, and more.

• Non-working spend represents the cost of producing marketing content. It is what happens behind the curtain to bring it to life. It includes almost anything that doesn’t fall into working spend but enables “working spend” activities, such as the budget allocated to pay for agency talent, assets and other costs associated with developing and producing content.

The ratio between the two is the metric that historically has been used to determine how efficient advertisers are at managing their marketing investment. In theory, advertisers are better off when non-working spend is as low as possible, ensuring most of the marketing dollars are being used to drive performance.

Could this ratio be outdated?

The use of such formulas to guide marketers on proper marketing budget allocations has been under fire for a number of years. Many consider it outdated and flawed for several reasons:

• Lack of standard definition.

Although the concept of working can easily be associated with media expenditures, non-working spend is less clear. Non-working spend often refers to the strategy and planning, messaging and content creation, research, production, and overall execution of a marketing campaign. Assigning expenses as working or non-working can be subjective and may not accurately reflect their real impact. In the digital age, it’s especially challenging to distinguish between them. For example, digital ads may have both creative and technology-related costs intertwined.

• Decoupling of agency services.

Historically, working spend has been tied to paid media. A simple 80% working to 20% non-working ratio was the default allocation methodology when one agency handled all work. In that

world, this rule made everything simple and predictable. However, this changed drastically when agencies decoupled these capabilities. When combined with the significant growth of digital media, this led to reduced paid media budgets.

• Profound change in media landscape.

The complexity and resources required to execute work in a fragmented and diverse marketing ecosystem — grouped under non-working spend — increased considerably. Advertisers saw the size of the pie of both owned, such as a website or ecommerce platform, and earned, often associated with social media, increase significantly.

Agency fees and other resources required to manage them increased proportionally. This drastically changes the working/non-working balance. A brand advertiser that successfully built a campaign without relying as heavily on paid media would hurt themselves if they were to downsize their non-working resources to maintain their ratio. When compared to historical trends, this formula is proving to be useless and detrimental to effective resource allocations and budget management in an increasingly digital and ecommerce landscape.

• Over-simplification.

Working and non-working spend analysis often oversimplifies the complexities of resource management and advertising effectiveness. This can lead to overlooking important nuances. An over-simplified approach tends to prioritize cost-cutting over strategic decision-making. While reducing non-working spend can be beneficial, it may lead to underinvesting in critical components of advertising, such as creative development and quality production.

• Over-emphasis on efficiency and short-term performance.

The instinctive inclination to reduce non-working spend must be constrained. Focusing solely on cost efficiency can neglect the importance of effectiveness and harm marketing efforts. Even if a campaign is cost-efficient, it may not achieve its intended objectives. Over time, excessive cuts to non-working spend can lead to a decline in the quality of creative and production, which can negatively impact brand perception and long-term success.

• Lack of industry benchmarks.

Most clients have their own definition of what they consider working and non-working. Comparing one brand’s allocation mix to another’s is like comparing apples and oranges. Advertisers have unique go-to-market strategies, ways to handle production and content development and different methodologies for media mix allocation. Establishing benchmarks and trying to compare companies with such diverse approaches is futile.

• Over-indexing on paid media.

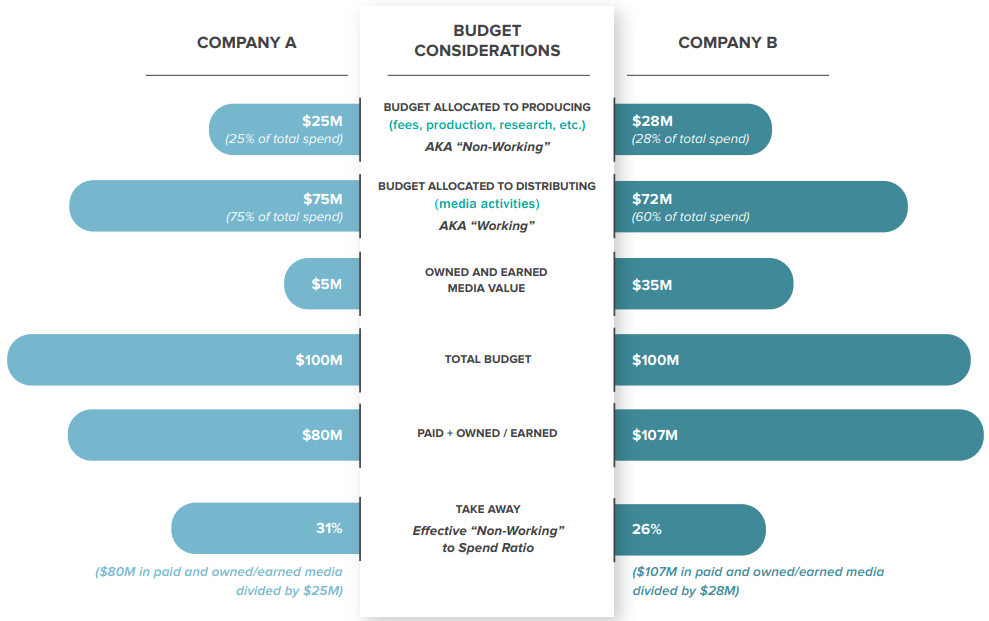

Some non-working costs, such as agency fees, may contribute indirectly to campaign success through strategic guidance and creative input. Some clients rely heavily on paid media while others invest aggressively in owned and earned media (for example, a company’s website properties, brand content vehicles or social platforms). Whenever advertisers shift spending from mass-reach paid advertising channels to a more content-rich, highly targeted type of execution, they are justified in spending more on production and fees. To further illustrate that point, consider the following two fictional companies shown in the figure on the following page. Company A might appear to be the most efficient at first glance, with only 25% of its spend on producing versus distributing, compared to 28% for company B. However, when factoring both paid and owned/earned media when comparing its spending allocated to producing assets, it shows that company B is far more effective, despite spending more than company A.

The WFA’s Brand investment decisions: Evolving beyond working/non-working report developed in partnership with MediaSense in November 2021, highlighted Burger King’s Whopper Detour Campaign, which was awarded several Cannes Lions & Effie Awards. An omni-channel approach, powered by data, content and consumer experience — relying heavily on non-working investments and less on paid media — resulted in 1.5m app downloads and $37m in earned media. This example illustrates the importance of balancing the two investment types and the risks of hindering marketing efforts by underfunding non-working resources.

Why do advertisers still use this formula?

Today, consulting firms and analysts agree that this traditional approach to working and non-working spend is obsolete and borderline dangerous without guardrails. It drives the wrong conversations and can lead to unwanted outcomes. You hear of advertisers looking to restructure their budget and land an 80/20 working to non-working ratio, often mandated by upper management. This top-down approach doesn’t lend itself to a meaningful or rational way to rationalize resource allocations. In fact, no preset ratio works.

In the January 2021 WFA report, WFA Benchmark: Global budget setting & use of working/non-working ratios, 81% of their members reported always or occasionally using a working and non-working spend ratio in their organization. Only 28% feel that the working/non-working methodology is not the best way to handle spend allocations. No one seems to agree strongly that it is the best metric, but the majority agree or disagree somewhat (33% and 31% respectively). In other words, alternatives are lacking. Budget owners often think of non-working spend as a necessary evil, misrepresented or undervalued. As a result, they frequently attempt to cap these expenses or look for ways to reduce them, without sacrificing too much the quality and effectiveness of the work itself. In their mind, the lower the amount of non-working, the better.

Yet most advertisers agree that non-working spend increased significantly in recent years for the right reasons. Microsoft’s Senior Director of Global Agency and Financial Management Caitlin Kaplan said it so brilliantly, “The ‘non-working’ part is what makes the ‘working’ work.”

The idea is pretty intuitive and easy to understand from a conceptual perspective. However, in practice, the concept has many limitations and often leads to disastrous outcomes if misunderstood and misused. Tom Finneran, former 4A’s EVP of Agency Management Services, put it best, “The notion of effectively controlling marketing costs by capping agency and production spending and any other ‘non-working’ expenditures to invest in working media dollars may, in fact, be penny wise and pound foolish, given the dynamics associated with today’s marketing environment.” Using the prior year’s budget, studying the competition’s allocation as baseline or using your gut are not much better. Advertisers are aware of the limitations of this budgeting approach. If some leaders still rely on this formula, it’s because few reliable alternatives have emerged.

Everyone is asking: What is the right ratio?

I could retire now in St. Barts if I got paid a dollar every time I’ve heard the question, “What is the right ratio?” Instead, I’m still in the U.S. answering the same question from anxious clients looking to rationalize their investment decisions. They are not to blame. They crave data to show they are spending wisely and responsibly. Some push their organizations to adopt zero based budgeting, leading with a bottom-up approach instead. But for those looking for a top-down method, the question remains: what is the right ratio?

Although there is no “right” ratio, past research has attempted to bucket marketing expenditures to understand spend standard cost allocations. Some studies, like Percolate’s The Hidden Cost of Marketing, suggest that the average non-working spend can consume more than 40% of the average advertising budget or 20% of the marketing budget. Note that advertising typically represents 48% of all marketing expenditures. In such studies, companies were allocating 24% of budgets to non-working spend and the average ratio of non-working spend varied by discipline. For example, 50% for traditional advertising, 43% for brand publishing and 42% for social, programmatic and website/ecommerce.

The 2021 WFA research points to an average working spend ratio of 7:3 (68% working to 32% non-working). The ratio varies geographically and by individual market, by business units (based on the type of work) and based on the type of media. In Advertising Production Resources’ 2020 Content Production Strategy: What’s the Average Working to Non-Working Budget Ratio for Today’s Modern Marketer?, the creative production efficiency consultancy provides this rule of thumb for a range of total spend on creation, development, production (non working):

• 10-12% for traditional mass media

• 15-20% for banners

• 55-60% for mobile/social

There is no shortage of studies or firms sharing a point of view on what should be the ideal ratio. Yet, the answer lies in a more systematic, organized approach to budgeting and a handful of critical best practices.

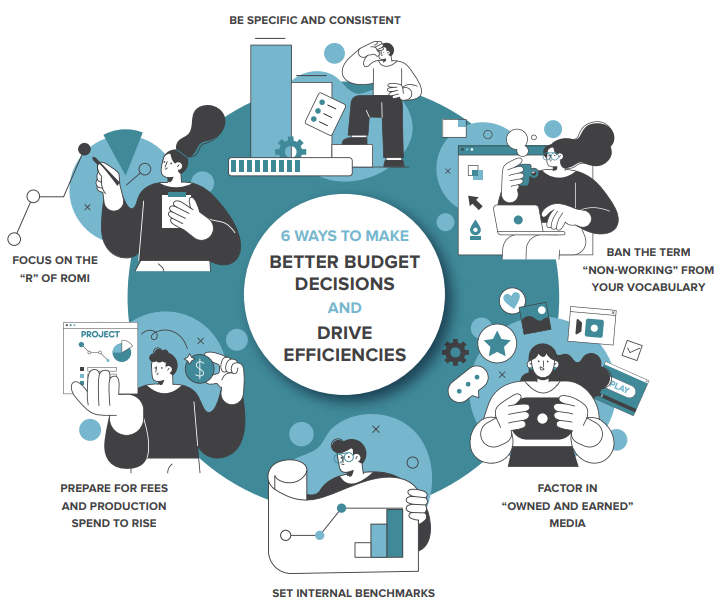

Six effective ways to make better budget decisions

Years of experience working with the world’s largest advertisers has taught me that following the six principles in the following figure yield more efficient use of marketing budgets and improve decision making.

1. Be specific and consistent

Whenever you look at expense categories and associated ratios to measure trends over time to make decisions about the level of efficiency desired, make sure you define each expense category in enough detail to make any discussion or decision as informed as possible. Develop a framework that relies on readily available data sets. Consistency is key as well, especially if you look at data over an extended period.

2. Ban the term “non-working” from your vocabulary

Stop referring to expenses associated with producing content as non-working. The amount of spend dedicated to production, agency fees, strategy or research should not be labeled as non-working or unproductive. It creates the wrong internal perceptions, diminishing the importance and value of the creative and talent required for the entire brand investment. Who would want to invest in something called non-working? If managed wisely, the expenses allocated to producing versus distributing work should be considered strategically important and one of the most productive uses of a marketing budget. Not having the right amount of allocated budget might seriously compromise the quality and effectiveness of the work distributed through various media channels. No one wants to spend massive budgets to send poor content to the wrong audience. Instead, consider using terms such as deploy for working and build or develop for non-working.

3. Factor in owned/earned media

As marketing budgets continue to shift to less traditional media channels and digital spend, so do the opportunities for brands to engage audiences and create content and experiences that go far beyond paid media. As illustrated earlier, brand advertisers should incorporate the value of their owned and earned media channels into their spend allocation analysis to get a broader, more holistic understanding of what’s needed in terms of content development and production to support maintaining and feeding these channels. So, make sure your “working media” definition includes paid media, earned media and owned media. In some instances, advertisers should also include martech investments that are about the placement and distribution of assets. Only then will they truly appreciate the rightful allocation of their budget resources.

4. Set internal benchmarks

External benchmarks do not work well in the absence of an industry definition or standard. Comparisons are futile and are often used as a validation exercise rather than a true attempt at discovering opportunities to better manage brand investments or improve business ROI calculations. However, setting internal benchmarks makes excellent sense because the company can evaluate how its allocations change over time and then drive specific activities around efficiency that can be reported on accurately.

5. Prepare yourself and others for non-working costs to rise

This is very challenging. It’s difficult for a CMO to explain to non-marketers at the C-suite level that they need to boost fees and production to support the expanding volume of assets and content created due to the increasing number of media channels. Yet, this is a reality for most brands that are exploring alternative means of reaching consumers and relying less on traditional media channels. Perhaps some of these channels are free or very inexpensive — owned and earned channels. However, creating quality, high-performance content for them is not. The cost of quality and expert talent, and the emphasis on proprietary data and tools is also on the rise, which adds to the increase in agency fees. And some clients may want to incorporate their martech investments in the content, development or production of assets such as Generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Digital Asset Management (DAM) capabilities.

6. Focus on the R of ROMI

Most companies focus on tightening marketing spend because it is based on a set of reliable expense categories that can be easily tracked and reported on. Although everyone wants marketing to be more ROMI (return on marketing investment) driven, the reality is that the “R” part of ROMI is much harder to define and measure. However, no one disputes that spending more to gain exponentially more is reasonable. Most CFOs would gladly allocate more spend to marketing if they could be ensured a certain return on their investment. Brand advertisers have more to gain by focusing their energy on ROI analysis than only spend analysis.

Moving forward with a new approach

We must revisit this obsolete approach to budgeting and realize that unless properly calibrated, it can be mishandled like any other tool. Tracy Allery, Nestle USA’s former Director of Marketing Procurement Business Partners summarized it best, “With the right structure, we will be able to continue to both compare spending and inform ROI. Our investments in marketing have moved beyond outdated ‘working’ and ‘non-working’ classifications.”

This type of Deploy versus Develop analysis has merit if done properly to compare and contrast investments (by business or geographically) made within an organization. It’s meant to be used as another dial, a sort of top-down indicator. But it is not meant to scientifically overrule enlightened discussions between marketing, procurement and finance or a sound brand investment strategy and analysis.

Next time you are analyzing your budget or looking to drive efficiency, consider agency fees and production activities as underleveraged sources of value creation and performance. I also recommend setting joint objectives with your agencies and identifying/ actively addressing the many areas of waste and inefficiencies in your existing engagements. If you do, you are more likely to improve the efficiency of your brand investment significantly. Develop/ Deploy (formerly, working/non-working) spend analysis can provide useful insights into cost allocation, but it should be used only as part of a broader framework for budget decisions and management by ROI. It’s important to balance cost efficiency with effectiveness, and regularly reassess budget allocations and how they contribute to your organization’s success.